Equine science article highlight: ‘The Effect of Short Term Prevention on the Subsequent Rate of Crib-Biting in Thoroughbred Horses’

By Paul McGreevy and Christine Nicol

Equine Vet Journal, Supplement 27, 1998

This equine science highlight article is very thought-provoking from the horse welfare and facility design perspectives. Equine stereotypies, including crib-biting, are those repetitive behaviour patterns that seemingly have no function. For many of these invariant behaviours the scientific research is still ‘out’ as to their cause and the extent of the detrimental effects on the horse’s welfare.

Possible contributory factors include equine stress and boredom where the stereotypes serve as a coping mechanism due to the horse’s management and/or environment, a lack of foraging opportunities, digestive problems and/or a genetic predisposition. This more extensive topic and its application to facility design will be explored another time.

This week’s highlight article’s specifically studies the behavioural consequences for horses if they are prevented from cribbing. The research has important implications for design as there is great scope for improving horse welfare via their built environments.

The article’s findings include that “the level of stereotypic activity after prevention was significantly higher than its original level.” This ‘post inhibitory rebound,’ i.e. the horse performs it with more intensity than prior to its short-term prevention, reflected a rise in internal motivation to crib-bite during the time it was stopped. The article summarises that “behaviours that exhibit this pattern of motivation are generally considered functional; and it has been argued that their prevention may compromise welfare.”

This is the aspect we could consider in terms of horse facility design and its relationship to horse welfare.

It is apparent that the design of many modern facilities has moved towards an effort to restrict stereotypical behaviours, sometimes with the intention of controlling this perceived ‘undesirable’ aspect of the horse’s behaviour. This is evident where the stable’s design objectives include limiting the physical edges the horse can seize with its teeth. The provision of steel door and window edges, metal capping and sheeting over timber are commonly detailed as they are a less favoured construction material for some horses to seize.

Let’s think about facility design for cribbing from a horse-centric approach.

Let’s propose we have a stable environment which optimises horse welfare with its visual and tactile connections to other horses, appropriate ventilation, the provision of a high fibre diet and daily access to pasture, but for whatever underlying reason, the mature horse still cribs habitually.

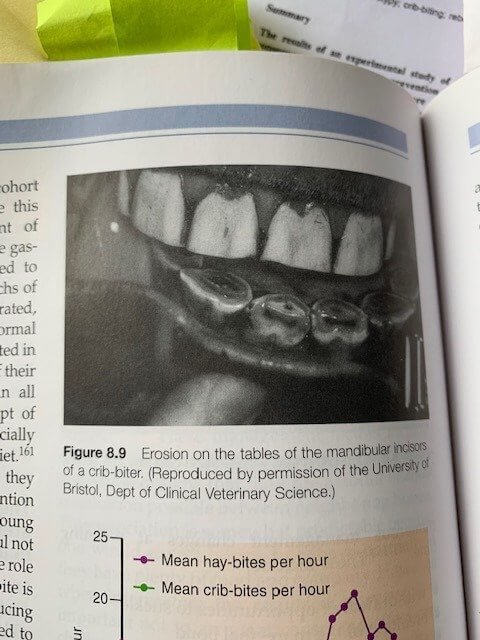

Let’s consider this mature horse and their need to express this behaviour when it is confined. Provided they do not suffer from any ill-effects welfare-wise as determined by veterinary professionals, how could we integrate safe cribbing opportunities instead of removing the edges completely or covering timber ones with metal which may damage their teeth.

It follows on that by preventing this mature horse from cribbing is a welfare issue that increases the negative experience of the horse, in the spirit of the Five Domains model, we should be rethinking every design element of the stable through a horse welfare lens - no matter how small a part it seemingly plays - like the design consequences of the top edge of a stable door.

In accordance with the article’s recommendation that “all affected horses have access to adequate foraging opportunities and allowed to crib bite.” It further suggests the provision of ‘cushioned cribbing-bars throughout the horse’s environment’ to limit the damage done to the cribbing horse’s incisors by a lifetime of cribbing.

As well as the cushioned type, a suitable timber may also be considered another option. This purpose designed element may also diminish our concern for teeth wearing and damage on metal where the horse continues to crib regardless of the hard steel capping or structure. Consideration of the timber species is recommended so that it does not easily splinter and crack and cause potential injury to the horse. This cribbing element does not in any way need to be structural nor offer the horse a stable environment to be completely chewed apart.

As for the argument that this may cause unsightly damage of the building, maybe the provision of this cribbing element becomes a part of the building’s overall intention to accommodate horse welfare requirements, just as the provision of fresh air and water is. Maybe the design of the cribbing element could offer easy removal and replacement where ‘wear and tear’ renders it no longer effective, required or safe. This idea could also be extended to cribbing rails along portions of fences as part of the built environment too.

Now this may be a controversial notion as some people do not like to enable the occurrence of any stereotypes or ‘stable vices’ as they are commonly and negatively referred to. However, if there doesn't seem to be any harm or performance disadvantage for this behaviour, and particularly if the cribbing habit was developed much earlier on in the horse’s life and is part of the individual horse’s repertoire of behaviours, maybe there is more harm caused by limiting its ability to safely crib in its stable environment.

Some scientists and behaviourists support this idea of allowing the horse to crib

Take a look at Dr. Andrew McLean's, Equitation Science International - ESI video on this very topic and his thoughts of its harmlessness in the mature horse. The responsive design of the built environment for cribbing is a valid concept given the reports of it prevalence ranges from 2-8% of horses.

See: What is cribbing/windsucking? Why do horses do it, with Andrew ...

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BUghMxIUfVk

The provision of cribbing elements in the built environment may not be the answer for every circumstance and we really need to look at the facility design within the individual context and consider the further research on stereotypic behaviour. However, it’s worth putting the idea forward as part of our rethinking horse facility design approach in order to optimise the positive experiences of the horse and the flow-on positive effects for the owners, trainers and handlers associated with each individual equine.

It is not that we at Equitecture Horse Facility Design promotes the establishment of stereotypic behaviour in horses and the horse community really needs to continue to discuss all the factors that lead to this in the first place, but where the habit is already hard wired, let’s look at providing for that horse an outlet for their behaviour in the designed environments.

Photo sources:

Cribbing horse in stable: www.horseandhound.co.uk

Teeth: 'Equine Behaviour' by Paul McGreevy, Saunders, 2004.